Outside Ankara, there are other fabrics in Africa you’ve probably never heard about. Yet for decades, one fabric has dominated the stage so completely that we sometimes joke in Yoruba, “o wo Ankara, o jẹ semo” — if you’re not wearing Ankara, there’s no food for you at the party. That’s how central it has become to celebration, identity, and style.

But Africa’s textile story is much deeper than the vibrant wax prints we know today. Long before European traders brought factory-produced prints to West Africa, local weavers, dyers, and embroiderers were creating fabrics that carried history in every thread. Some fabrics were woven for kings and warriors, others dyed with earth and plants, and many told stories of lineage, power, and spiritual belief.

This is a journey into the forgotten fabrics — ten rare African textiles beyond Ankara, each with centuries of artistry and heritage behind them.

1. Akwete – The Loom of Igbo Women (Nigeria)

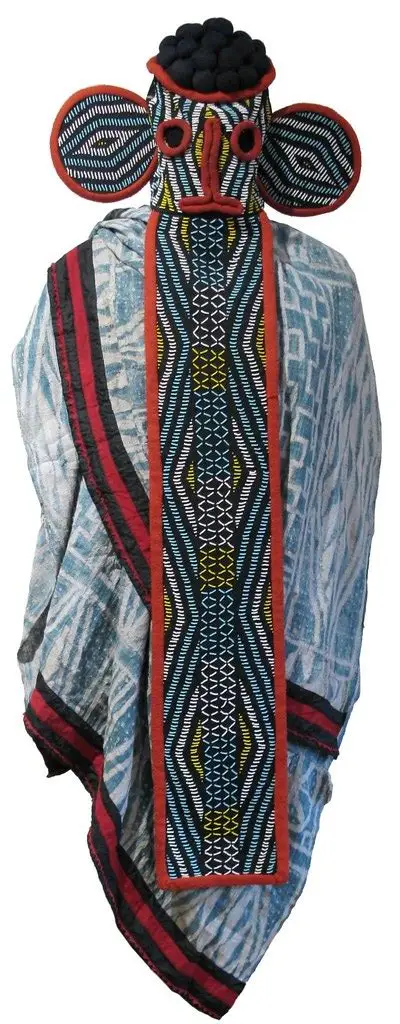

Akwete cloth is the pride of Igbo women weavers in Abia State, where the town of Akwete gave the fabric its name. For centuries, women have sat at narrow looms, turning cotton, raffia, and sometimes hemp into striking cloths with bold, geometric motifs. The designs aren’t just decorative; many carry symbolic meanings tied to wealth, power, and spirituality. In precolonial times, raffia versions were used for warriors’ attire or masquerades, while softer cotton cloths were worn daily or presented in ceremonies.

Akwete also appeared in dowries, royal burials, and as symbols of status. Today, the fabric remains a cultural marker, worn by women at weddings, festivals, and political gatherings, while also finding space in global markets as fashion accessories and décor pieces. Its survival speaks to the resilience of indigenous textile knowledge and the pride of Ndoki women who still weave these threads of history.

2. Kuba Cloth – Royal Geometry (DR Congo)

Kuba cloth from the Democratic Republic of Congo is one of Africa’s most distinctive textiles. Woven from raffia palm leaves, the fabric is first created by men, who weave rough base cloths. Women then transform these panels into masterpieces through embroidery, appliqué, and cut-pile techniques that give a velvet-like texture. The result is cloth marked by complex geometric motifs, each design inspired by nature, cosmology, or cultural belief. Historically, Kuba textiles were made for royalty and nobility, worn as skirts, tribute cloths, or ceremonial regalia in the Kuba Kingdom.

Beyond fashion, they also served as currency in marriage and trade. Today, Kuba cloth has moved beyond its royal courts, admired worldwide as art. Museums and collectors prize the pieces for their bold aesthetics, while contemporary designers rework Kuba patterns for clothing, wall hangings, and accessories. It remains both a symbol of status at home and an ambassador of Congolese artistry abroad.

Read: What Do You Really Know About Aso Oke?

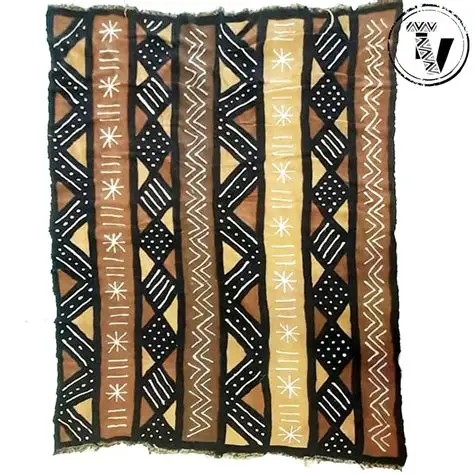

3. Mud Cloth / Bogolanfini – Stories in Earth (Mali)

Bogolanfini, widely known as mud cloth, is a textile with deep Malian roots. Made from handspun cotton, the fabric is dyed with a labor-intensive process using fermented mud and plant-based solutions. Each pattern is not random decoration but a coded language — certain symbols represent protection, healing, or key moments in life like marriage and initiation.

Originally worn by hunters and warriors as a spiritual shield, mud cloth later became important for women, particularly in childbirth and social ceremonies. In the 20th century, Malian artists and designers helped bring bogolanfini to global attention, making it a symbol of cultural pride. Today, mud cloth is everywhere: in fashion runways, interior design, and global décor markets. Yet, it is still being made in Bamana communities, where artisans continue to pass down the intricate dyeing traditions that tie earth, heritage, and identity into every piece of cloth.

4. Barkcloth – Woven from Trees (Uganda & Beyond)

Barkcloth is one of Africa’s oldest textiles, crafted not from fiber crops but directly from trees, especially the Mutuba fig tree in Uganda. To produce it, the inner bark is stripped, soaked, and repeatedly beaten with wooden mallets until it becomes soft, pliable, and wearable. Its natural reddish-brown tone is distinctive, though artisans sometimes enhance it with dyes. Historically, barkcloth held immense cultural value.

Among the Baganda people of Uganda, it was considered sacred, worn by kings, chiefs, and priests during rituals and burials. It also carried everyday uses as bedding, curtains, or wrappings. The craft declined under colonial bans but has since been revived, with UNESCO recognizing Ugandan barkcloth as intangible cultural heritage. Today, it appears in cultural festivals, contemporary fashion, and even eco-design projects. Beyond fabric, barkcloth stands as a living reminder of human ingenuity in transforming nature directly into culture.

5. Shweshwe – The Blueprint of Southern Africa

Shweshwe is instantly recognizable for its tightly patterned, indigo-dyed cotton prints that once came to Southern Africa through European trade but have since become thoroughly Africanized. Its name traces to King Moshoeshoe I of Lesotho, who popularized the fabric in the 19th century.

Over time, the prints — once imported from Europe — became localized through South African production, earning shweshwe the nickname “the denim of South Africa.” Traditionally, it holds strong associations with Sotho, Tswana, and Xhosa communities. Newly married women often wore it as a marker of status and respectability, while brides and initiates continue to feature it in ceremonies. Today, shweshwe remains widely used, from everyday skirts and aprons to tailored wedding dresses and men’s attire.

Designers across the continent and diaspora reimagine it in modern cuts, keeping the heritage alive. Shweshwe’s survival proves how a traded cloth became a lasting identity marker for Southern Africa.

6. Kikoi – The Coastal Wrap (East Africa)

Along the Swahili coast, where trade winds once carried spices, stories, and strangers, another fabric became a cultural anchor: the kikoi. Unlike many African textiles, the kikoi is woven, not dyed—a cotton sarong whose simplicity hides its versatility. Traditionally worn by Swahili and Maasai men, it has expanded into a unisex staple: a wrap for women, a sling for babies, even a makeshift towel for travelers. Its colors—bright, striped, sun-drenched—mirror the vibrancy of Zanzibar markets and Kenyan beaches.

But the kikoi is more than just coastal fashion; it is living proof of Africa’s maritime legacy, shaped by centuries of exchange. Today, artisans in Tanzania and Kenya keep the tradition alive, ensuring the kikoi remains both functional and fashionable. If Ankara is for the party, the kikoi is for life itself—soft, adaptable, and always present where ocean meets land.

7. Faso Dan Fani – Cloth That Speaks (Burkina Faso)

Burkina Faso’s Faso Dan Fani carries a name that translates as “woven cloth of the homeland,” and with it, an identity woven in pride. More than fabric, it is a national symbol—one that gained legendary prominence under revolutionary leader Thomas Sankara, who urged Burkinabé to wear their own cloth as an act of resistance and dignity.

Handwoven in strips on traditional looms, Faso Dan Fani tells stories in color and pattern, with motifs that whisper history and strength. Every thread carries the resilience of a people determined not to fade into imported sameness. Today, it is still a marker of pride—seen in state ceremonies, cultural festivals, and everyday wear. To wear Faso Dan Fani is not just to dress, but to declare: this is who we are, this is where we come from. It is a cloth that still speaks, centuries on.

Read: Kente – Ghana’s Symbolic Cultural Brilliance

8. Baoulé Cloth – The Ancestral Weave (Côte d’Ivoire)

From the heart of Côte d’Ivoire comes Baoulé cloth, a fabric that bridges past and present. The Baoulé people, descendants of the Ashanti, carry centuries of weaving heritage on their looms. Hand-dyed cotton threads—colored with indigo and plant-based dyes—are carefully arranged to create textiles used in ceremonies and communal gatherings. Each motif is more than decoration; it encodes meaning, linking the wearer to ancestors, community, and the land itself.

Historically reserved for special occasions, Baoulé cloth holds high cultural value, embodying both artistry and spirituality. To see its bold lines and deep hues spread across a courtyard is to witness tradition unfolding in cloth form. Even as modern fashion evolves, artisans in Ivorian villages continue to preserve the ancestral patterns, ensuring the weave remains a symbol of dignity and belonging. In Baoulé cloth, heritage is not remembered—it is worn.

9. Toghu / Ndop Cloth – Royal Embroidery (Cameroon)

In Cameroon, two textile traditions merge into one powerful symbol of identity: Ndop and Toghu. Ndop, the older practice, is a handwoven indigo cloth, created through intricate resist-dye techniques. Toghu, on the other hand, takes the fabric further—transforming it with flamboyant embroidery once reserved for royalty. Rich in color, bold in detail, Toghu was historically worn by kings and queens, its stitches a language of power and prestige.

Over time, what was once restricted to palaces became an emblem of cultural pride for Cameroonians across regions. Its global breakthrough came in 2012, when the Cameroonian Olympic team marched into London’s stadium dressed in Toghu—bringing royal heritage to the world stage. Today, Toghu is worn at weddings, festivals, and diaspora celebrations, carrying with it the weight of tradition and the flair of modern African confidence.

10. Gara Tie-Dye – Sierra Leone’s Living Canvas

Sierra Leone’s Gara fabric is not just dyed—it is performed into being. Originating in Makeni, Gara is made through raffia-tied resist dyeing, using natural colors that seep into cloth with unpredictable, breathtaking patterns. Each piece is one of a kind, a canvas where improvisation meets tradition. Historically, Gara carried spiritual weight, used in Bundu or Bondo initiation rites for young women—a symbol of transformation, beauty, and community.

Today, its role has expanded, adorning markets, fashion runways, and tourist stalls. Yet its essence remains the same: a living art form born of Sierra Leonean creativity and resilience. Bright blues, earthy browns, vibrant reds—each shade carries the spirit of the soil and the people. To wear Gara is to wear a story written in dye, bound in raffia, and unraveled only when the fabric meets the world.

Our Fabrics, Our Identity

How many of these fabrics have you heard of before?

Chances are, outside of Ankara, only a few. Yet, woven across Africa’s vast landscape are fabrics far older, rarer, and deeper than the prints we often see at parties and runways.

These textiles are not just clothing. They are living archives—repositories of memory, artistry, and resilience. From Faso Dan Fani’s message of resistance to Gara’s tie-dyed creativity, from Toghu’s royal embroidery to Baoulé’s ancestral weave, each fabric carries more than color; it carries a story. They are languages written without words, reminding us that African fashion is not a trend but a legacy.

But legacies must be preserved. If we do not celebrate and integrate them into modern fashion, these fabrics risk becoming museum relics rather than living traditions. The responsibility is ours—to wear them, to support the artisans, and to ensure the relevance of these fabrics in today’s global fashion narrative.

At RefinedNG, we tell these hidden stories—of Africa’s fashion, food, culture, and innovation. Follow us to discover more treasures like these fabrics that remind the world: Africa is not just vibrant, it is timeless.